Historical Society supports restoring Rosenwald School

Published 4:46 pm Monday, July 29, 2019

FREDONIA — There were no empty seats inside the Fredonia Community Clubhouse Sunday afternoon as a large crowd gathered to hear a two-part presentation.

“Traveling Schoolmarm” Susan Webb was there to discuss the Rosenwald School program, and New Hope Foundation Board Chairman George Barrow talked about the current effort to restore the building to its original architectural plan.

The clubhouse served as the host site for the Chattahoochee Valley Historical Society’s quarterly meeting. Both the clubhouse and the New Hope Rosenwald School are having their centennials this year. Both were built in 1919 and opened as community schools that year. The Fredonia School opened on Oct. 8 of that year. To mark the centennial, a big party will be taking place at 7 p.m. EDT on Tuesday, Oct. 8 of this year. Both the clubhouse and New Hope School will be welcoming visitors on the annual Heritage Day, set for Saturday, Nov. 2.

An Iowa native, Webb has a passion for the one-room school house. At one time, there were more than 12,000 of them in the Hawkeye State. According to a state law, there had to be one such school every two miles. It served a state that’s always been known for agriculture.

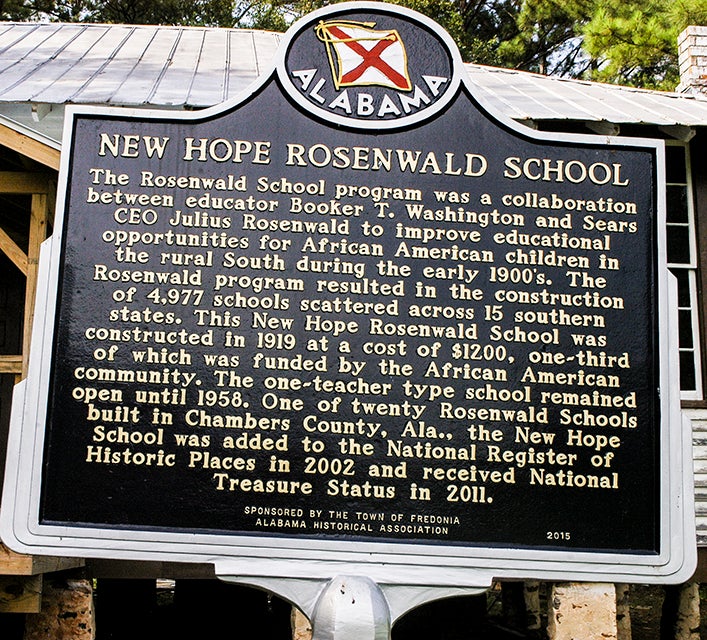

The Rosenwald Schools program was enormously important for the African Americana children in the real south in the early 20th century. Close to 5,000 of them were constructed in 15 Southern states. Close to 220 teacher homes and more than 160 shop buildings went through this program. A total of 20 Rosenwald schools were built in Chambers County. The New Hope School is thought to be the only one still standing. In 2002, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places and received National Treasure Status in 2011.

“The Rosenwald Schools would not have existed without Booker T. Washington,” Webb said. “He was the genius behind this program. His long-time friend, Julius Rosenwald helped with the funding and local communities built them.”

The first one was built in Loachapoka in 1913 and the final one in 1932.

Webb asked if anyone in the crowd had ever attended a Rosenwald school. One hand went up, that of George Barrow. He attended one in Five Points and is now heading up the effort to renovate the Fredonia building as close as possible to its original state. Thus far, he and other board members are on track to have it fully restored within the year.

The Rosenwald schooling he received as a child gave Barrow a jumpstart on a good education. He’s now a retired engineer, having had a career in the automotive industry.

Webb said Booker T. Washington encouraged fellow African Americans to believe in themselves and to have the self confidence to make a difference in their community. Washington was a gifted speaker and was well connected among philanthropists, among them Julius Rosenwald.

He met him in Chicago in 1911. Rosenwald took a liking to him immediately. The son of German-Jewish immigrants to the U.S., Rosenwald had experienced prejudice and sympathized with anyone else who had. Washington impressed upon him that much needed to be done in the rural South to see that black children received a decent education. At the time, Rosenwald was president and board chair of Sears, Roebuck & Co. and was worth an estimated $150 million. He believed that he had a moral duty to help others and established the Rosenwald Fund, which supported a wide range of worthy causes such as public schools, colleges and universities, museums, hospitals and clinics, relief agencies, scientific research and such programs as the YMCA and the Jane Adams’ Hull House.

At the turn of the 20th century, black children in the rural south attended school in one-room shanties, church basements or farm buildings, most of them without desks or books.

To address this, Rosenwald committed large sums of money for the construction of new schools, affectionately known as Rosenwald Schools. It was done on a matching basis. A school building that would cost $1,200, for example, would get $400 from the Rosenwald Fund, $400 from the state and $400 through local fundraising.

“Local fundraising would come from many sources,” Webb said. “Some people would make donations after selling a bale of cotton. Others would make donations after selling vegetables.”

There were distinctive features with Rosenwald schools. In most cases, they were built on two-acre sites and from detailed floor plans. The signature feature were the large banks of windows that would let in lots of light. Most of them had a library, cloak rooms, 30 feet of blackboards, movable walls, desks lined up in rows, a well and outdoor privies for the boys and girls.

Robert Taylor was the master architect and builder. He was the first African-American to graduate from MIT and the first African American to be a fully accredited architect. His great-granddaughter, Valerie Jarrett, recently served in the Obama Administration.

Other philanthropists helped in the cause of helping education for black children in the rural South. Anna T. Jeanes, a wealthy Philadelphia Quaker, funded the Jeanes Program, which enabled skilled teachers to work with black children is rural areas.

Washington did not live to see the full impact of the Rosenwald Schools program.

“He died in 1915,” Webb said. “I believe he overwhelmed himself. He was traveling all the time and trying to generate support for what he wanted to do.”

Webb said that Chambers County residents should appreciate the historic treasure they have with the New Hope Rosenwald School.

“There are so few of them left,” she said. “You have a real jewel in your presence. It’s something that can inspire the younger generation. We need to get them involved in appreciating where we came from.”

Barrow credits two people, Webb and the late John Hoggs, for getting involved in restoring the New Hope School. He said that he’d previously heard Webb talk about Rosenwald Schools and their historic importance.

“I had gone to one and didn’t know it,” he said. “Susan was an inspiration that helped get me involved.”

Mr. Hoggs was well known as a city council member, educator and coach in West Point. He has a city park named in his memory today.

“He was the second person to inspire me about this,” Barrow said. “He had attended the New Hope School as a child and was involved in founding the 501 (c) (3) foundation in 2002. In his later years, he asked me if I would take control on this and I told him I would. He was staying in Newnan when I went to visit him. He was in the hospital at the time, but I met with his wife who gave be a box of documents. It contained lots of information about the foundation and New Hope School. He died the next day.”

The current board, said Barrow, has a simple mission — to preserve and restore the New Hope Rosenwald School.

“We are restoring it at present, but we’d like for it to be a community center and a museum,” he said. “We want to promote the legacy of the Rosenwald School initiative. People don’t know enough about it today.”

The building, said Barrow, was built according to Robert Taylor’s Plan No. 11. The school closed in 1958. For a few years following the closure, an elderly black couple lived there and did some remodeling to the building, taking out the front porch, the library and cloak rooms. In 1969, ownership was transferred to the New Hope Baptist Church, which is next door on County Road 267. The church has since turned it over to the New Hope Foundation, which is heading up the restoration effort.

“Some major modifications were necessary,” Barrow said. “We’ve put in a front porch, front entrance doors, the library and cloak rooms,” he said. “Our goal was for them to be as much like they were originally. It’s the only one still standing in Chambers County. That’s what makes it so special.”

Barrow said he’s very proud of the fact that one of his great aunts, Viola Zachry, was one of the first teachers at the New Hope School in the 1920s.

Grants from the Alabama Historic Commission and the Coosa Valley Rural Community and Development Association helped in the renovation effort.

“We are very appreciative of that,” he said. “It helped us get off to a good start. This is not a fast job. It’s not like building a new structure. We want to make sure we do it the right way and not the fast way.

Restoring the windows has not been easy. Some were donated from Lanett Mill, but they were too heavy to be used alongside the original ones still left. They have to be a certain weight to keep the window balanced where it can be more easily opened and closed. “The original glass was lighter and thinner,” he explained.

They also had a big problem to address near the rear chimney, where much leaking had taken place in recent years.

“It’s a good thing we got to it when we did,” Barrow said. “It would have worsened with time and could have ruined the whole building. We had to strip the wall and rebuild it. We had to put in a new beam that went from one end of the school to the other.”

Barrow said he is well pleased with the windows.

“There are some lovely views from inside the building,” he said.

Something new that will be going in is a handicap ramp. It will be on the front side next to the porch and will make the building compliant with the Americans With Disabilities Act.

CVHS President Malinda Powers presented Barrow a $500 check on behalf of the organization to help with ongoing renovation work.

“Thank you,” Barrow said. “This will go a long way to help us with what we are doing. We still have a lot of work to do, but we are getting there. We’ve gotten most of the major work done.”