Progress 2024: Archivist keeps local history alive

Published 10:30 am Saturday, March 2, 2024

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

If a picture is worth a thousand words, an archive is priceless. An archive refers to either a place where public records or historical materials are preserved. It can also mean the material itself. To archive is a complex process, but in short, means to preserve something.

What a museum is for artifacts an archive is for documents. The Cobb Memorial Archive is where documents, photographs and occasionally artifacts are preserved to tell the story of Chambers County and the surrounding area. Piecing together this story, and preserving history, is the job of an archivist. Robin Watson is the archivist for Cobb.

The Archivist

Watson thought she would be an archeologist and studied classical archeology major at Florida State University. Like many college graduates, she left school unsure of the path she had planned to take. Watson went to a graduate student fair at her school, where she met an advisor at Auburn University, Clint Lovelace.

“Hey, do you like history? And maybe don’t want to go through a PhD in a very specific field, he’s like, consider archives,” Watson said.

She did consider archives. Watson got her master’s in history with a graduate certificate in archives. As a part of the program, Watson got an internship with Cobb in 2012 processing boxes of documents for the archive.

You’re actually like handling the stored materials that would be used by someone looking to write a paper or publish a book. They’re gonna come to an archives to find the primary sources. So I really enjoyed it,” Watson said.

After graduating from Auburn, a position at Cobb opened up and Watson has been the archivist ever since.

How to Archive

To preserve something in an archive, there are steps that need to be taken. First, and most importantly is called appraisal. Most of the things in an archive are donated by members of the public.

“[Appraisal] is something every archivist is going to agonize over all the time. It is actually making the decision from when something walks to the door,” Watson said. “Does this fit with our collecting policy? Is it unique? Does it speak to a part of history that maybe is underrepresented or that we don’t have much of? Archival appraisal is trying to decide what to keep and kind of what the rationale is behind it.”

The appraisal part is wear much of the dirty job aspect of archiving comes in. Many of the donations that come to the archive have not been stored correctly or are worse for wear.

“Usually the circumstances surrounding a donation are either folks are moving or someone’s passed away and cleaning up the house. So kind of like important changes in life that prompted us to think about, what am I going to do with this stuff?” Watson explained.

Sometimes the materials that come in have been stored outside or in ways that expose them to the elements. Watson said pests love paper, so when documents have sat in a garage for decades it is not unusual for photos or papers to be degraded.

Once intaking a donation, the appraisal can take days depending on how much material there is to go through. Watson takes this step very seriously. Sometimes she will keep things that go well with a collection they have, say the World War II materials.

Other times materials can fill gaps in the archive, with documents and photos of a part of history that is underrepresented. For families or individuals donating to an archive, it is often the last chance to save someone’s memories. Watson said the responsibility to decide what is worth preserving and what will be thrown away and forgotten has kept her up at night.

“You just sort of will wrestle with these decisions. Because if it’s not going to stay here in like, and I can’t find another archive that it would be appropriate for… then it’s probably going to be lost forever. So that is a weighty decision to make,” Watson said.

Once the decision has been made on what stays, the ordering of the information happens. Watson pulled out a recent box of donated materials she received from the son of a Valley High teacher. It had photos of field trips to the mills and old assignments from her students.

“We try to keep things in original order based on the principle that whoever originally collected or created these materials know them better than I ever will,” Watson said. “So if they imposed an order on and there’s a logic to it, that makes everything kind of work better together as a whole, rather than me trying to separate it.”

If there is no discernable order, the archivists make one. It could be grouped by type of material, like photos, or by subject. So for the teacher, the grouping could be by family history if there are more personal items, and by teaching career and high school.

Once everything is organized, the storing of the donation begins.

“Tools of the trade would be acid-free folders and acid-free boxes. So this is to give materials a better microenvironment,” Watson explains holding what looks like any other box. “A lot of paper-based materials have acid and lignin especially, so that’s what makes things kind of brittle and dry or turn yellowish with time.”

She explains that acid-free storage keeps that acid from leaching out, providing a buffer for the paper. Watson adds that a huge part of preserving is having a climate-controlled environment, which means materials should be stored somewhere with little fluctuations in temperature or humidity.

Watson advises individuals to store cherished items saying, “keeping things safe from sunlight, and from extreme hot or cold or moisture. If you can keep things in a closet, away from sunlight, you’re ahead of the game.”

A big no in preserving is lamination. In the short term for materials that you don’t mind losing or getting rid of later, lamination is fine. However, Watson warns against lamination for long-term storage.

“Remember most things that are paper there’s going to be some sort of acidity to it. And that acidity wants to come out. When you heat it up really hot in a laminator and then trap it in plastic, there’s nowhere for that acid to go. So it just kind of deteriorates from the inside out,” Watson explained.

When everything is properly stored, a finding aid must be written. This is a document that gives some background on the donations, what subjects it includes, and overall what the collection has. This part is important so if someone comes in asking about a family history or a document that could help in research for a local topic, the archivist can find primary sources easily.

While archiving is, of course, a big part of the job, an archivist has many other duties.

Putting the Puzzle Together:

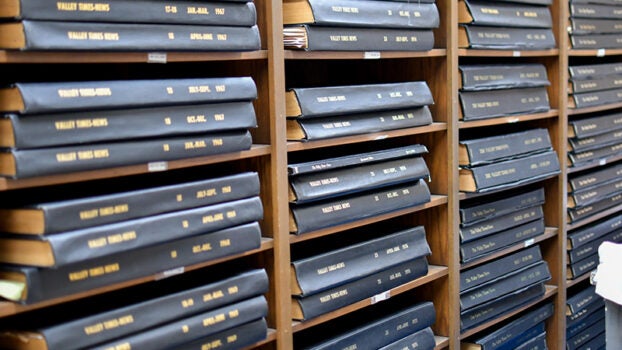

The point of appraising, sorting and preserving these materials is to be able to piece the history of an area together. Whether it is for someone coming in to learn about a family member or do some research for a book or paper, an archive is a library of primary sources.

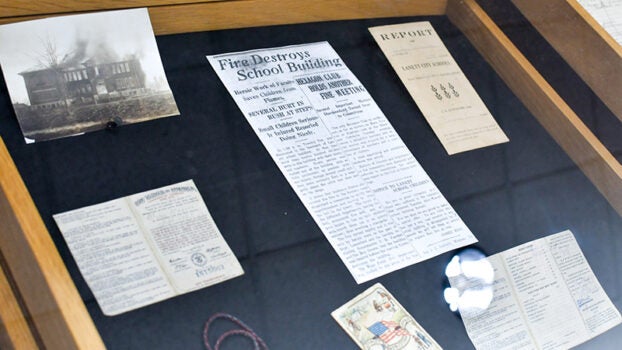

The archivist not only acts as a locator of specific sources for others but also as a detective, putting together the pieces, photographs and documents, of the story. One example of this is through curating exhibits.

If you were to walk into Bradshaw Library, where Cobb Archives is located, there would be two rows of display cases. The rotating exhibits display the materials of a collection. When looked at together, they tell a story of an event, person or place.

“It’s always kind of fun to dig into the collection and the story behind local events,” Watson said. “That’s probably my favorite thing to do.”

Currently, Watson is working on an exhibit on Camp Lanier.

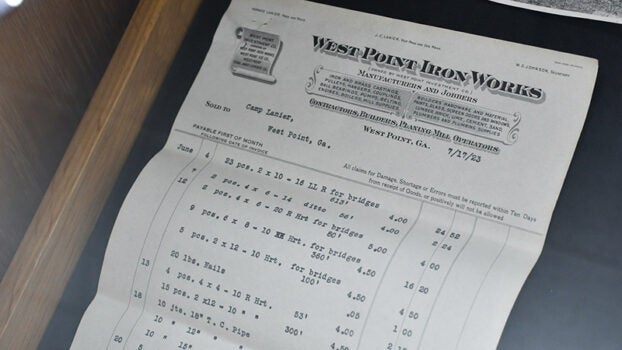

“What do we have that tells the story… we have papers that show Camp Lanier. So these are building supplies from July 1923,” Watson said holding a bulleted document with the camp’s logo at the top.

Not many people would look at a supply list with as much wonder as Watson. But, as she explains the nails and pipes that were used to construct the camp it is surprisingly easy to get excited. The page is history, telling the story of a moment in time.

“You’re seeing all that was used…I just love that we have something that speaks to the very beginning,” Watson said smiling.

Another important job is outreach. An archive survives through people, which means they must know about it. For a while, Watson wrote an article for the VTN about an interesting collection the archive had. However, like so many things during COVID-19 it was put on hold. There is also a Cobb Archive Facebook page.

Watson’s true passion lies not in the organization of historical materials but in the sharing of them. She works closely with the library and local schools to get history into the hands of the public.

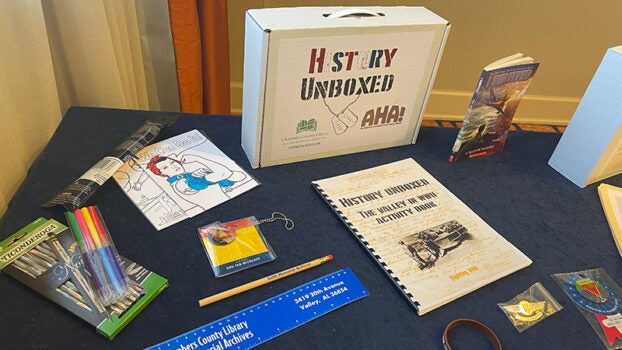

One example of this is history kits. Watson, together with Valley High Media Specialist Ellen Emfinger, created these boxes for students to learn about history.

“I put together something on like Local World War II primary sources, things that I thought might be a good addition if it wasn’t already in the curriculum, or just kind of bolster it,” Watson said.

The box had activities that incorporated primary sources like letters from local couples during WWII or pictures of soldiers, an ‘I survived’ storybook, dog tags and other items. The students would go through the workbook informed by the sources in the box.

Watson said after introducing the boxes it sparked some students to talk with parents and grandparents about their history. One parent reached out to say they found out about a family member who had battled polio in the early 20th century due to talks started by the history kits.

“It’s interesting that this can kind of inspire like this family conversation and uncover family history. So that’s, that’s an aspect of that, that I really enjoyed,” Watson said.

Value of an Archive

Watson said the two main groups they get in the archive are researchers and people hoping to learn about family history. They have authors and students requesting sources on local topics, like the mill or the courthouse, for example. But many are looking for their own personal history.

“At times, the value [of an archive] is a little bit more personal, but not any less important. If you’re doing like family history, your genealogy, and you uncover something, I think you can almost maybe discover a part of your own identity or discovered part of yourself that maybe you didn’t know or fully understand,” Watson said.

An archive is a library of people’s lives. When put into collections, the materials tell the story of a person, group of people, place, or time. In the acid-free boxes at Cobb are papers and photos someone collected and kept because they were important enough to keep. An archivist may not always keep everything, but what they do remains important.

“Come to the archives for the questions that Google can’t answer. There’s a lot of richness in the history here. And I feel like that kind of comes to life through you know, your own curiosity but also in some of our collections,” Watson said.